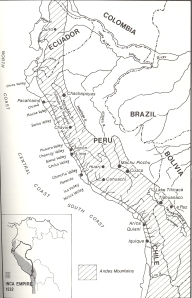

The Inca are one of the most well known pre-Columbian societies of Sout h America. Perhaps one of the most interesting parts of Inca culture, extending from 1476 to 1634 B.C., is their funerary rituals, including mummification (Cockburn and Cockburn 143). Unlike the Chinchorro mummification, Inca mummification was restricted to those of high social ranks, including kings and clan leaders and high nobles. Lower status members of society were simply buried, with little mortuary treatment. The Inca Empire ranged over a vast territory, and the mummification practices varied from region to region.

h America. Perhaps one of the most interesting parts of Inca culture, extending from 1476 to 1634 B.C., is their funerary rituals, including mummification (Cockburn and Cockburn 143). Unlike the Chinchorro mummification, Inca mummification was restricted to those of high social ranks, including kings and clan leaders and high nobles. Lower status members of society were simply buried, with little mortuary treatment. The Inca Empire ranged over a vast territory, and the mummification practices varied from region to region.

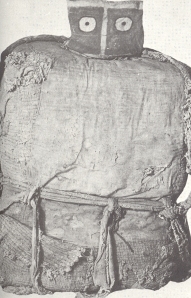

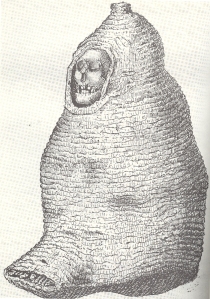

In the central highlands (Condesuyo), the deceased were placed in a burial tower or sepulcher. The body was eviscerated, and balsamic substances were added to aid in preserving the body (Cockburn and Cockburn 145). The mummification process in the lowlands and coastal regions (Yungas) was slightly more complex. The organs and the flesh were not always removed, but when the flesh was taken off the body, it was buried next to the dead in ceramic vessels. The bodies themselves were covered in a cotton shroud and wrapped in cloth and ropes, forming a “mummy bundle.” The upper portion of the bundle was painted and decorated to suggest a face, suggesting that they played some societal role after death. Until the final burial, the mummies were displayed in their monumental sepulcher and participated actively in the lives of the living. The Inca were eventually buried with several grave goods, including clothing, food, and ornamentation (Cockburn and Cockburn 145).

the dead in ceramic vessels. The bodies themselves were covered in a cotton shroud and wrapped in cloth and ropes, forming a “mummy bundle.” The upper portion of the bundle was painted and decorated to suggest a face, suggesting that they played some societal role after death. Until the final burial, the mummies were displayed in their monumental sepulcher and participated actively in the lives of the living. The Inca were eventually buried with several grave goods, including clothing, food, and ornamentation (Cockburn and Cockburn 145).

Check out this link for a video showing the details of a mummy bundle!

http://ngm.nationalgeographic.com/ngm/0205/feature5/multimedia1.html

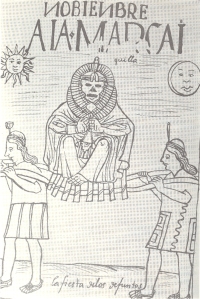

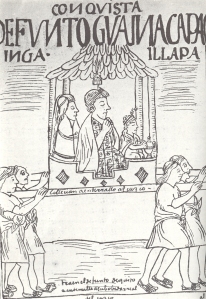

Like the Chinchorro, the Inca mummies (especially the kings) did not cease to participate in the lives of the living after their deaths. For example, the mummies of kings were cared for by the royal family; they were fed, clothed, and involved in other daily activities. Furthermore, the Inca mummies were repeatedly brought to festivals and ritual events where they take part in their own mortuary cult. This suggests that the Inca elite did not truly die upon their biological death. Similar to Chinchorro culture, the lives of Inca mummies extended past that point, and they continued to participate in Inca culture .

.

Like the Chinchorro, Inca mummies were perhaps worshiped as ancestors, or huacas. Huacas were essentially just sacred things, including anything from mountains, to pottery, to the bodies of rulers. They were venerated for their associations with fertility and their power to regenerate life. The surviving Inca community communicated with various huacas through prayers and offered dedicatory offerings to ask for assistance or advice. Archaeological evidence of offerings and sacrifices found on mountains known to be huacas supports this claim (Ceruti and Reinhard 2). In this way, although beliefs about an afterlife might have been at play, the Inca mummies were more for the aid of the living than an attempt at immortality for the deceased.

Some scholars also believe that the production of not only Inca mummies, but also Andean mummies before them, was in part brought about by both economic and political factors. “Based on present evidence, one can tentatively state that religious cults and magical motives, some clearly derived from political and economic contexts, were all contributing factors in Andean mummification practices,” (Cockburn and Cockburn 154). Mummies of royalty and elite members of society could have been displayed not solely for religious purposes, but also as signs of the lasting power of the society. They also would have justified those elites or royals in their positions; if they could trace their lineage to these visible, public ‘ living monuments’, they were worthy of their position in that society. Since the Chinchorro had a much simpler society, in this way, the two types of mummies differ. However, we know so little about the Chinchorro culture, we cannot completely rule out the idea that their mummies had some economic role or motivation behind them.

It can be speculated that as the Inca Empire was expanding, it incorporated the beliefs and practices of conquered people. As Richard Latcham states in “Atacameño Archaeology,” “old beliefs die hard” (Latcham 609). Although the Chinchoro were a much simpler and older society than the Inca, their burial practices did not completely disappear with their culture. Very similar mortuary practices can be seen in the Atacameño people, who inhabited the northern part of Chile slightly after the time of the Chinchorro (Latcham 612). In a manner strikingly similar to the Chinchorro, “the [Atacameño] mummies were wrapped in skins of animals and sea birds,”  in an extended position. Latcham traces these mummification practices from the Atacameño directly to the Inca (1936). Given the similarities between the mummies of the Chinchorro and the Atacameño peoples, in addition to the remarkably parallel mortuary rituals between the Chinchorro and the Inca, it is highly likely that the Inca mummification practices and rituals were influenced, at least in part, by the Chinchorro.

in an extended position. Latcham traces these mummification practices from the Atacameño directly to the Inca (1936). Given the similarities between the mummies of the Chinchorro and the Atacameño peoples, in addition to the remarkably parallel mortuary rituals between the Chinchorro and the Inca, it is highly likely that the Inca mummification practices and rituals were influenced, at least in part, by the Chinchorro.

Sources:

Ceruti and Reinhard (2005). “Sacred mountains, ceremonial sites, and human sacrifice among the Incas.” In Arcaeoastonomy: the journal of astronomy in culture (University of Texas Press).

Latcham (1936). “Atacameno Archaeology.” In The American Anthropologist (38.4: 609-619).

![aleutian mummy[1] Aleutian Mummy being exhumed](https://chinchorromummies.files.wordpress.com/2010/11/aleutian-mummy1.jpg?w=640)

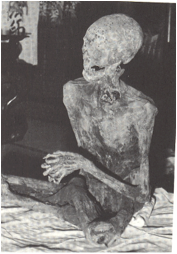

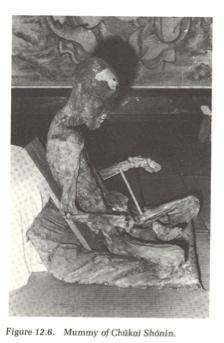

Ancient Cultures). In order to assist Maitreya in accomplishing this feat, the priests waited for his coming in their earthly form, as preserved mummies. When viewed in this light, it is almost as though these Japanese priests practiced altruistic suicide. Their death was an excruciatingly long and painful process, the last few years of their life essentially consisting of dehydration and starvation. And although many of these mummies were eventually enshrined and worshiped as gods, it is likely that the priests did this not for themselves but for the other followers of Buddhism. Not only would the priests be available during the coming of Maitreya to help save mankind, but many temples also claimed that the priests believed that their deaths would alleviate the sufferings of the people. Furthermore, this mummification practice was certainly not always successful. The body, buried for over three years before being exhumed for worship, would often deteriorate, indicating that the priest had failed to become Sokushinbutsu. If this were the case, the body would be immediately reburied, and the priest would never be worshiped. This fact further stresses that the priests were not doing this for their own longevity and prospects of being a deity. They apparently truly believed in their altruistic sacrifice.

Ancient Cultures). In order to assist Maitreya in accomplishing this feat, the priests waited for his coming in their earthly form, as preserved mummies. When viewed in this light, it is almost as though these Japanese priests practiced altruistic suicide. Their death was an excruciatingly long and painful process, the last few years of their life essentially consisting of dehydration and starvation. And although many of these mummies were eventually enshrined and worshiped as gods, it is likely that the priests did this not for themselves but for the other followers of Buddhism. Not only would the priests be available during the coming of Maitreya to help save mankind, but many temples also claimed that the priests believed that their deaths would alleviate the sufferings of the people. Furthermore, this mummification practice was certainly not always successful. The body, buried for over three years before being exhumed for worship, would often deteriorate, indicating that the priest had failed to become Sokushinbutsu. If this were the case, the body would be immediately reburied, and the priest would never be worshiped. This fact further stresses that the priests were not doing this for their own longevity and prospects of being a deity. They apparently truly believed in their altruistic sacrifice.

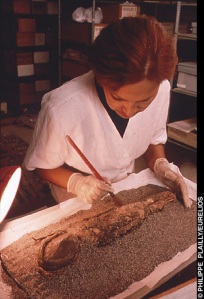

into something else– something more in the form of art. In mummification, bodies were taken apart, then reassembled and decorated with ash paste and color. The mummies were also adorned with wigs and sometimes masks. Clearly, the visual aspect of these creations was important. Bernardo Arriaza, a scholar of physical anthropology, explores the idea of the mummies as ritual art in his article, “Making the Dead Beautiful: Mummies as Art” (

into something else– something more in the form of art. In mummification, bodies were taken apart, then reassembled and decorated with ash paste and color. The mummies were also adorned with wigs and sometimes masks. Clearly, the visual aspect of these creations was important. Bernardo Arriaza, a scholar of physical anthropology, explores the idea of the mummies as ritual art in his article, “Making the Dead Beautiful: Mummies as Art” ( to these ritual objects seems to imply more activity. Arriaza also suggests that these mummies were used in processions. Not only were the mummies functioning ritual objects, they were portable pieces of art. This explanation could account for the “wear and tear”, but what follows is the question of why. Why were the dead mummified and perhaps carried in processions? We have mentioned that the Chinchorro were non-discriminatory in their mummification; everyone could undergo this mortuary treatment, regardless of sex, age, social status, etc. Were all of the mummies, then, used to the same extent? Were the processions for all the dead?

to these ritual objects seems to imply more activity. Arriaza also suggests that these mummies were used in processions. Not only were the mummies functioning ritual objects, they were portable pieces of art. This explanation could account for the “wear and tear”, but what follows is the question of why. Why were the dead mummified and perhaps carried in processions? We have mentioned that the Chinchorro were non-discriminatory in their mummification; everyone could undergo this mortuary treatment, regardless of sex, age, social status, etc. Were all of the mummies, then, used to the same extent? Were the processions for all the dead?